Healing Leaky Gut: Strategies for Stronger Digestion

Ever wonder why your doctor rolls their eyes at the mention of "leaky gut" to your doctor, while your holistic practitioner swears by it as the root of all ills? Welcome to one of medicine's most fascinating controversies.

Known scientifically as increased intestinal permeability, leaky gut bridges cutting-edge research and clinical gray areas. In this article, we'll dive deep into the evidence, demystify the science, and arm you with practical, rigorously supported strategies to fortify your gut. Whether you're battling digestive woes or simply optimizing your health, understanding this barrier could be a game-changer.

The Science of Your Gut's Security System

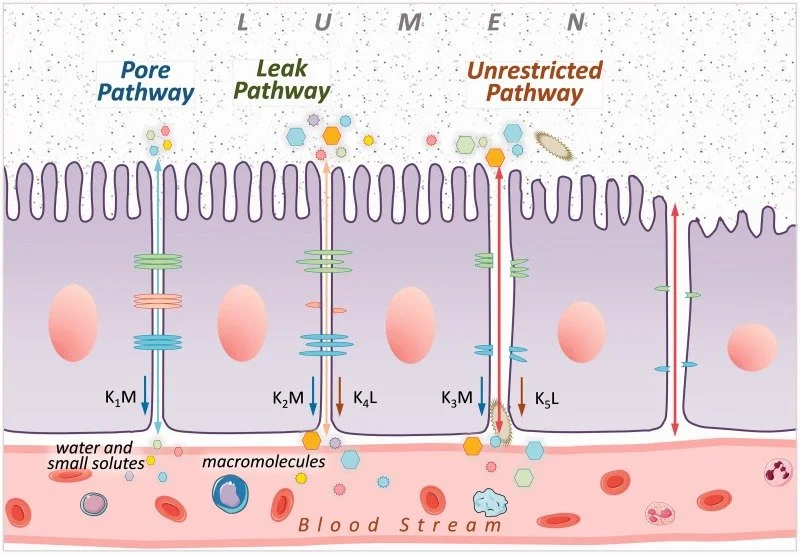

At its core, your intestinal barrier is a marvel of biological engineering—a selective fortress that lets nutrients in while keeping toxins out. It comprises three essential layers: a protective mucus coating, tightly packed epithelial cells, and vigilant immune defenses. Within the epithelial layer, three paracellular pathways regulate what crosses this boundary:

Leak Pathway: Allows larger molecules to pass through tight junctions, regulated under normal conditions.

Pore Pathway: Selectively transports ions and small molecules via tight junctions.

Unrestricted Pathway: Linked to disease states, such as cell death, allowing bacteria and other harmful substances to pass through the intestinal barrier unchecked.

Picture your intestinal barrier as an extraordinarily sophisticated security system. Testing for intestinal permeability employs various methods, each with its limitations.

Zonulin Testing, which measures zonulin levels in blood or stool, has shown inconsistent results as high serum zonulin is more closely linked to metabolic markers than specific gut issues, leaving its role in diagnosing leaky gut uncertain.

Emerging markers like lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, a toxin produced by certain microbes, are under investigation but are not yet reliable for clinical use.

Elevated fecal calprotectin levels indicate the migration of neutrophils to the intestinal mucosa or even to the gut lumen in case of gut barrier disturbances.

The Benchmark Test

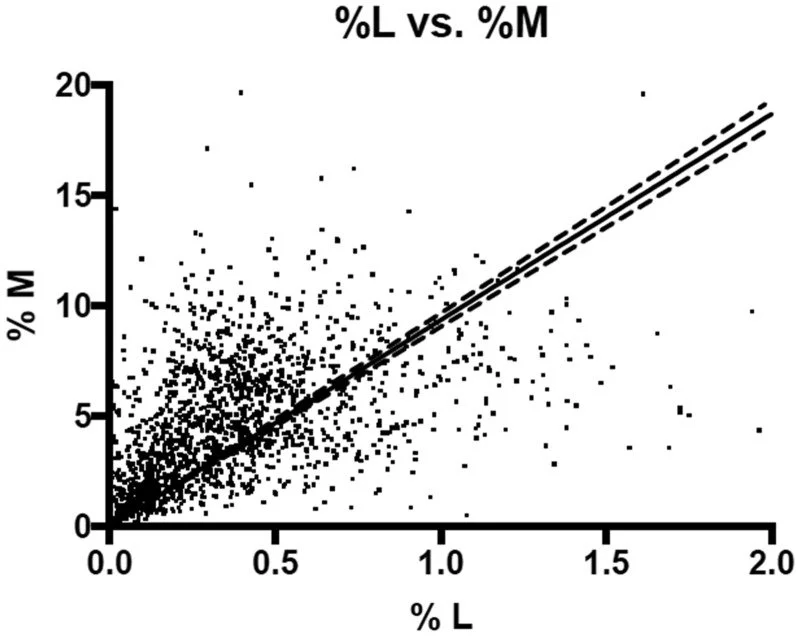

The Lactulose/Mannitol Test is the most widely utilized method for assessing intestinal permeability, primarily measured through urine collection.

This test employs two non-metabolized sugars: lactulose, a larger molecule, and mannitol, a smaller one. The fundamental premise is that lactulose is expected to pass through damaged areas of the intestinal barrier, while mannitol is thought to traverse the intestinal wall through healthy epithelial pathways.

Fascinatingly, interpretations vary globally, highlighting the need for context in diagnostics. A Brazilian study in Scielo found healthy controls at 0.07% lactulose recovery, celiacs at 0.15%, and Crohn's patients at 0.42%. Yet thresholds differ according to different regions:

Australian labs flag concerns at 0.30%.

U.S. standards start at 0.90%.

Europeans often land in the middle.

At 0.60%, you might sail through a U.S. checkup but trigger alarms Down Under. This underscores why personalized, evidence-based approaches matter over one-size-fits-all labels.

This scatter plot shows results from a lactulose–mannitol gut permeability test, with each dot representing one person’s percentage recovery of lactulose (x‑axis) and mannitol (y‑axis). A regression line and its confidence bands illustrate the overall positive relationship between how much of each sugar is absorbed and excreted in urine.

Leaky Gut's Far-Reaching Ripple Effects

Abnormal permeability isn't isolated to the gut. Research links it to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), where levels are elevated but milder than in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or celiac disease. In Crohn's, heightened permeability may even predict flares, pointing to its inflammatory role.

The connections extend further and are associated with asthma, autism, multiple sclerosis, and other non-GI conditions. This suggests leaky gut serves as a potential contributor to systemic inflammation. While causation isn't fully established, these correlations from peer-reviewed studies warrant attention.

Triggers, Timing, and Everyday Influences

Your gut barrier isn't static—it's dynamic and fluctuates according to your lifestyle choices. Common culprits like NSAIDs (ibuprofen, aspirin), alcohol, excessive saturated fats, and even vigorous exercise can temporarily heighten permeability. The upside is that removing these triggers often restores balance swiftly.

To proactively support integrity, science-backed supplements shine:

Zinc Carnosine (37.5-75mg daily): Bolsters tight junctions.

L-Glutamine (5-15g daily): Fuels cell repair.

Probiotics (10-20 billion CFU): Strains like Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG enhance barrier function.

Curcumin (500-2000mg daily): Delivers anti-inflammatory punch.

Colostrum (10-60g daily): Reinforces mucosal health.

The Power of Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) arise when gut bacteria ferment dietary fiber, positioning them as key metabolic regulators. They help manage weight, glucose control, insulin sensitivity, and triglyceride levels, while also fueling colon cells, strengthening gut barriers, and promoting epithelial repair. The primary SCFA here is butyrate, which serves as the main energy source for colon cells (colonocytes), accounting for 60-70% of their energy needs, while also helping maintain gut barrier integrity by promoting mucus production and tight junctions.

You can boost SCFA production with prebiotics like resistant starch, inulin, xylooligosaccharides, and arabinogalactan, which selectively nurture butyrate-producing bacteria. A thriving microbiome is essential here: Beneficial species such as Akkermansia muciniphila and butyrate-makers like Faecalibacterium, Blautia, and Roseburia enhance mucus production and tight junction regulation. In contrast, excess Proteobacteria can trigger inflammation and disrupt this delicate ecosystem.

Focusing on these microbes through diet and targeted prebiotics may be a cornerstone of gut resilience.

Prebiotics and Bacterial Growth

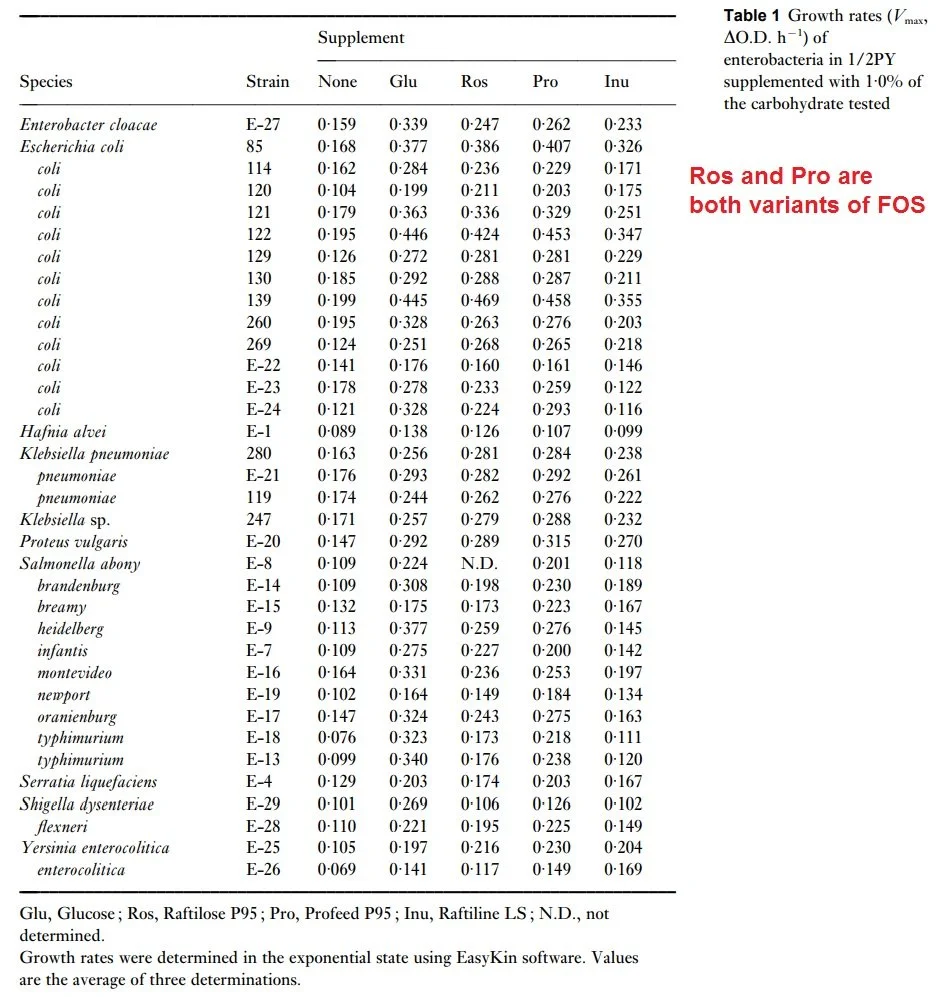

A landmark 1997 in vitro study in the Journal of Applied Microbiology tested how pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae strains grow on prebiotics like short-chain FOS and inulin, revealing patterns that support gut barrier integrity and overall microbiome balance key to preventing leaky gut.

These pathogens (e.g., E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella) often inflame the gut lining and weaken tight junctions, contributing to leaky gut where toxins leak into the bloodstream. The study showed most exhibit minimal growth on FOS/inulin versus baseline, allowing beneficial bacteria to dominate and produce SCFAs like butyrate for mucus reinforcement and epithelial repair.

This in-vitro (test-tube) growth-rate experiment measured how fast various bacterial species/strains grow when given 1 g/L (0.1%) of different prebiotic carbohydrates as their energy source. Higher number means faster growth per hour, which demonstrates that the strain consumes that substrate effectively.

Column Definitions:

None = no added carbohydrate (baseline growth on residual medium carbon)

Glu = Glucose (positive control – most strains grow well)

Ros = Raftilose P95 (short-chain FOS from acacia gum, arabinogalactan-rich)

Pro = Profeed P95 (another commercial short-chain FOS)

Inu = Raftiline LS (longer-chain inulin)

Takeaways for Real-World Gut Health

Many pathogenic/opportunistic Enterobacteriaceae grow poorly on FOS/inulin, but not all.

Strains like most E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Proteus, and Serratia show minimal or no uplift from baseline ("None") on Ros, Pro, or Inu—supporting selective bifidogenic effects where beneficial bacteria outcompete them.

Exception: Klebsiella pneumoniae strains often grow substantially better on short-chain FOS (Ros/Pro rates ~0.26–0.29 h⁻¹, comparable to or exceeding glucose), indicating they can ferment these prebiotics in isolation. This is strain-variable but notable.

Long-chain inulin (Inu) is generally the weakest stimulator across strains, including pathogens.

Ros and Pro (short-chain FOS variants) perform similarly and outperform inulin for most utilizers.

Pathogens like Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, and Serratia remain largely indifferent—excellent for selectivity against these.

| Goal | Best Prebiotics | Caution / Monitor For |

|---|---|---|

| Starve most pathogens | Short-chain FOS/inulin generally limit E. coli, Salmonella, Proteus, etc. (Hartemink et al., 1997) |

Klebsiella strains may utilize short-chain FOS in vitro; risk is higher in dysbiosis |

| Feed beneficial / probiotic bacteria | Short-chain FOS support strains like probiotic E. coli or Hafnia | Use long-chain inulin if preferring distal effects (deeper colon) |

| Klebsiella-dominant or SIBO cases | Pair with probiotics (e.g., certain Lactobacillus strains + prebiotics inhibit KPC-Klebsiella) (Tang et al., 2022) |

Avoid solo high-dose short-chain FOS if overgrowth is known; fiber absence promotes K. pneumoniae bloom (Anthony et al., JCI 2024) |

| General bifidogenic effect | Short-chain FOS > long-chain inulin; in vivo, prebiotics often suppress Klebsiella via competition and SCFA production | Context-dependent: dysbiosis or recent antibiotics increase risk (Anthony et al., 2024) |

According to this study, short-chain FOS is highly selective against most Enterobacteriaceae pathogens (starving Salmonella, etc.) while feeding some beneficials. Klebsiella pneumoniae is a notable exception, capable of robust growth on FOS alone.

However, our bodies behave differently than test tubes. In living systems, fiber tends to favor broad microbial recovery after antibiotics, limiting the ecological space available to pathogens like Klebsiella pneumoniae. Simple carbohydrates, on the other hand, can selectively fuel overgrowth during periods of gut stress or inflammation.

Evidence also points to a synergistic effect between diet and probiotics. Beneficial strains appear significantly more effective at suppressing Klebsiella when supported by fermentable fibers, suggesting that competitive metabolism and microbial byproducts—not probiotics alone—drive meaningful control.

Complex fibers support beneficial gut microbes that crowd out Klebsiella and produce acids that make the gut less friendly to harmful bacteria. Fiber-rich diets have been shown to reduce the spread of these microbes. Combining probiotics with prebiotic fibers enhances these effects and performs better than single-strain probiotics in animal models.

Typical doses (4–10g/day from foods/supplements like acacia gum or chicory FOS) remain a cornerstone for gut repair in balanced microbiomes but using stool analysis and monitoring symptoms when dosing helps maximize safety.

Safeguarding Your Gut During Antibiotic Use

Antibiotics save lives but can ravage your microbiome, leading to antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD). Evidence shows probiotics and prebiotics can mitigate this. Here's a research-informed protocol:

Pre and Post Recovery: Probiotic Powerhouses

Saccharomyces boulardii (e.g., Florastor): Slashes AAD risk by over 50% in kids and adults; curbs Candida overgrowth.

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG): Proven for AAD prevention, especially in children and during H. pylori therapy.

Nourish survivors with fibers like:

Inulin and FOS (4–10g): From garlic, onions, chicory, Jerusalem artichokes.

Galactooligosaccharides (3.5–7g): In legumes, chickpeas, lentils.

Acacia Gum (5–10g): Boosts bifidobacteria and lactobacilli.

Partially Hydrolyzed Guar Gum (5–10g): Enhances butyrate for healing.

Short-chain FOS (oligofructose, DP 2–9) ferments quickly in the colon's front section, fueling fast growth of good bacteria like bifidobacteria while producing SCFAs (e.g., butyrate) for quick energy and gut barrier support—but it can also mean more initial gas or bloating. Long-chain inulin ferments slower and steadier, spreading benefits further down the colon for longer-lasting effects on gut health.

Bringing It All Together

Increased intestinal permeability is measurable and biologically meaningful, with clear roles in GI disease and plausible links to systemic inflammation. That said, it's not a standalone diagnosis or a universal explanation for every symptom.

Gut barrier integrity depends on context, timing, and microbial ecology. Lab studies show how isolated microbes respond to specific fibers, but in living systems, fiber works indirectly. They reshape microbial communities, shifting metabolite production, and strengthening the barrier through diversity and balance.

This is why blanket advice—“take more fiber” or “avoid all fermentable carbs”—misses the mark. Prebiotic combinations each have distinct effects that depend on your existing microbiome, recent antibiotic use, and the presence of opportunistic strains like Klebsiella. Used thoughtfully, they're powerful tools for restoring resilience after stress or disruption.

The gut isn't broken; it's responsive. Remove obvious insults, feed the right microbes, and respect biological variability, and the barrier often repairs itself.

Bibliography

Wang, X., & Gibson, G. R. (1993). Effects of the in vitro fermentation of oligofructose and inulin by bacteria growing in the human large intestine. Journal of Applied Bacteriology, 75(4), 373–380.

Van Loo, J., et al. (1995). On the presence of inulin and oligofructose as natural ingredients in the western diet. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 35(6), 525–552.

Gibson, G. R., & Roberfroid, M. B. (1995). Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: Introducing the concept of prebiotics. The Journal of Nutrition, 125(6), 1401–1412.

Barboza Jr., M. S., et al. (1999). Measurement of intestinal permeability using mannitol and lactulose in children with and without diarrhea. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 32(12), 1499–1504.

Roberfroid, M., et al. (1998). Chicory inulin, oligofructose, and health. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 38(7), 538–543.

Hartemink, R., et al. (1997). Growth of the intestinal microflora from human infants on prebiotic fructo-oligosaccharides. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 83(5), 531–538.

Cummings, J. H., & Macfarlane, G. T. (2006). Short chain fatty acids. In Colonic Microbiota, Nutrition and Health (pp. 67–82). Chapman & Hall.

Van de Wiele, T., et al. (2004). Prebiotic effects of chicory inulin in the simulator of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 50(3), 333–344.

Van de Wiele, T., et al. (2007). Inulin-type fructans of longer degree of polymerization exert more pronounced in vitro prebiotic effects. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 104(2), 478–485.

Stewart, M. L., et al. (2008). Fructooligosaccharides exhibit more rapid fermentation than long-chain inulin in an in vitro fermentation system. Nutrition Research, 28(8), 526–531.

Tang, W., et al. (2022). The effect of Lactobacillus with prebiotics on KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13, 1050247.

Hecht, A., et al. (2024). A step closer to understanding how a diet high in simple sugars promotes Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 134(10), e180001.