To Lower Cholesterol…Or Not

Is High LDL Cholesterol Really Bad?

We've been conditioned to fear high LDL cholesterol, believing it to be the ultimate heart health villain. For many years, the prevailing view has been that high LDL cholesterol is the primary driver of heart disease, strokes, and other cardiovascular disorders. This view may be pervasive, but what if it’s incomplete—even harmful?

This comprehensive guide explores a body of research that challenges traditional cholesterol theories and reveals what truly matters for cardiovascular health.

Understanding Cholesterol Basics

What it is: Cholesterol is a waxy, fat-like substance that's found in all cells of the body. Your body needs cholesterol to make hormones, vitamin D, and substances that help you digest foods.

Where it comes from: Cholesterol comes from two sources: Your body makes it, and it's also found in animal-derived foods like meat, poultry, and dairy products.

The Different Types (Lipoproteins)

Because cholesterol doesn't dissolve in blood, it must be transported by carriers called lipoproteins. The main ones are:

LDL (Low-Density Lipoprotein): Often called "bad" cholesterol, high levels of LDL cholesterol contribute to plaque buildup in arteries.

HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein): Often called "good" cholesterol, HDL helps remove cholesterol from the arteries and back to the liver, where it can be eliminated.

Triglycerides: These are another type of fat in your blood. High levels of triglycerides, combined with high LDL or low HDL, are linked to an increased risk of heart disease.

The Cholesterol Hypothesis: What Traditional Medicine Has Taught Us

The cholesterol hypothesis suggests that LDL builds up in artery walls, forming plaques that narrow arteries and lead to heart attacks. However, emerging research is causing some researchers to propose a more nuanced understanding of how heart disease develops.

LDL is increasingly understood as more of an exacerbating factor than the primary initiator of heart disease. Think of it like this: LDL is like putting the wrong fuel in a car with a damaged engine. The wrong fuel makes the problem worse, but it didn't cause the initial engine damage.

New Research on Cholesterol and Heart Disease: The Vasa Vasorum Hypothesis

The most widely accepted explanation for atherosclerosis (plaque buildup in arteries leading to heart disease) is the "cholesterol hypothesis." It states that the process starts in the inner lining of the artery (the endothelium) due to:

Inflammation

High levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)

This damages the endothelium, allowing LDL-C, immune cells like macrophages, and other substances from the blood to enter the artery wall from the lumen (the interior of the blood vessel). Plaque then builds up inward, narrowing the artery.

Vladimir Subbotin's Vasa Vasorum Hypothesis

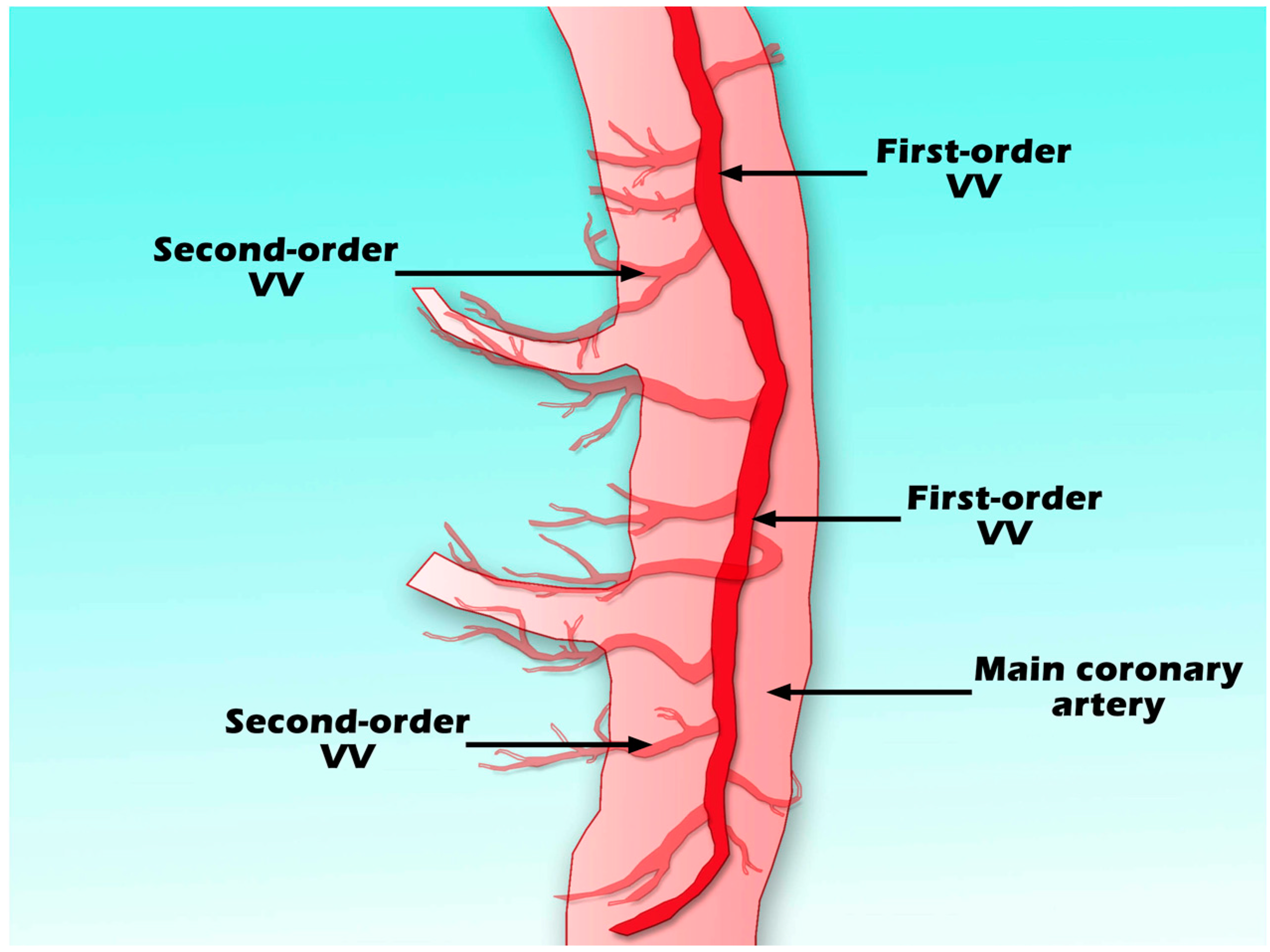

In a 2016 review published in Drug Discovery Today, researcher Vladimir M. Subbotin proposed a different origin for coronary atherosclerosis. He argued that plaque starts from changes in the vasa vasorum— the tiny blood vessels that supply oxygen and nutrients to the outer layers of larger artery walls.

Key Points of the Hypothesis

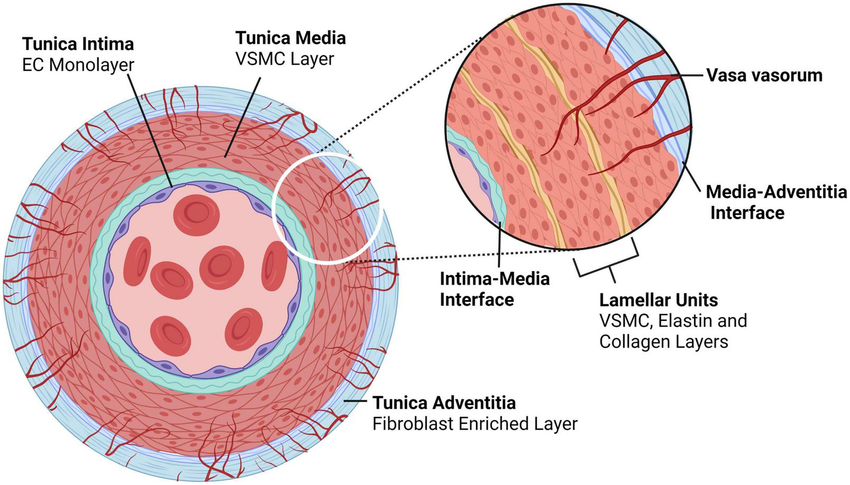

The tunica intima, the innermost layer of the artery, is thicker than often assumed and often shows diffuse intimal thickening (DIT), a normal structure made up of roughly 20–50 cell layers. In healthy patients, it has no blood vessels (avascular) and gets nutrients by diffusion from the artery's main lumen.

With age or other factors, the intima thickens excessively in a process called hyperplasia. This increases the distance for diffusion, causing low oxygen levels (hypoxia) in the outer (deeper) parts of the intima.

Hypoxia triggers new, leaky blood vessels to grow from the adventitial vasa vasorum into the deep intima, causing neovascularization.

These new vessels allow LDL-C, monocytes, and plasma components to leak directly into the outer intima, where they bind to proteins like biglycan. This starts lipid buildup and plaque formation from the outside in.

This explains the outer lipid deposition paradox in which early plaques show fats accumulating in the deepest intimal layers (near the media), not near the lumen as the traditional view predicts.

Supporting Evidence

Evidence from lab studies on human artery samples and animal experiments show that new leaky blood vessels from the outer artery layer (vasa vasorum) grow before cholesterol buildup or inflammation starts inside the artery.

Evidence from Human Artery Studies

Nakashima Y et al. (2007), published in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology.

Researchers examined coronary arteries from individuals aged 9 months to 40 years and found that the earliest atherosclerotic lesions (fatty streaks) formed deep within diffuse intimal thickening (DIT), adjacent to the arterial media.

Immune cell infiltration occurred later, with no early lipid accumulation near the lumen—supporting an “outside-first” model in which proteins such as biglycan trap cholesterol deep in the vessel wall.

Subbotin VM (2016), published in Drug Discovery Today.

Autopsy studies of healthy and early-disease coronary arteries show that the intima is naturally thick and avascular.

In early atherosclerosis, new microvessels grow inward from the outer layer in response to low oxygen, and initial lipid accumulation appears deep within the vessel wall rather than at the blood-facing surface.

Evidence from Animal Studies

Herrmann J et al. (2001), published in Cardiovascular Research.

Within just 2–4 weeks of being given high-cholesterol food, pigs began growing new vasa vasorum vessels in heart arteries—before any damage to the inner lining or endothelial dysfunction (blood flow problems).

The number of these outer tiny vessels jumped from about 3 per square millimeter to almost 5—a ~64% increase

At this early stage, the inner lining was still perfectly healthy with no reduced blood flow or damage. Only later (after 6–12 weeks) did the inner lining start to malfunction.

Challenging the Traditional Cholesterol Hypothesis: Key Evidence from Clinical and Epidemiological Studies

Evidence from large-scale studies and meta-analyses suggests that high LDL cholesterol may not be the primary or sole driver of heart disease in many cases, with factors like inflammation, metabolic health, and other mechanisms playing significant roles.

Normal LDL Levels in Heart Attack Patients

Large hospital databases reveal that most individuals hospitalized for heart attacks have LDL cholesterol levels considered "normal" or optimal by guidelines, highlighting limitations in relying solely on LDL as a risk predictor.

Sachdeva A et al. (2009). "Lipid levels in patients hospitalized with coronary artery disease: An analysis of 136,905 hospitalizations in Get With The Guidelines," American Heart Journal.

The study analyzed 136,905 hospitalizations for coronary artery disease (2000–2006) from the Get With The Guidelines database.

Key findings:

Average LDL cholesterol level on admission: 104.9 mg/dL

Nearly 75% of patients had LDL levels below commonly recommended targets for high-risk individuals (e.g., <130 mg/dL for many, and ~50% had LDL <100 mg/dL)

Only 21% of patients were taking lipid-lowering medications before hospitalization

These results suggest that relying solely on current LDL guidelines may fail to identify many individuals at high risk for coronary events, since most patients who experience acute events already have relatively "normal" or low LDL levels.

The Role of Inflammation Over Isolated Cholesterol Levels

Ridker PM et al. (2002). “C-Reactive Protein and Other Markers of Inflammation in the Prediction of Cardiovascular Disease in Women.” New England Journal of Medicine.

This landmark prospective study followed 27,939 initially healthy American women for a mean of 8 years to compare the predictive value of various risk markers for first cardiovascular events (heart attack, stroke, revascularization, or cardiovascular death).

Key findings:

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) was the strongest independent predictor of cardiovascular events among 12 tested markers, outperforming LDL cholesterol

Women with the highest hs-CRP levels had a relative risk more than twice that of those with the highest LDL levels

hs-CRP retained strong predictive power even in women with low or normal LDL cholesterol levels, identifying substantial residual risk not captured by lipids alone

The authors concluded that hs-CRP adds significant prognostic information beyond traditional lipid screening and that inflammation assessment improves risk stratification, particularly in individuals with otherwise favorable cholesterol profiles.

No Clear Link Between Saturated Fat Intake and Heart Disease

For decades, dietary guidelines have urged limiting saturated fats—found in foods like butter, cheese, red meat, and coconut oil—to reduce the risk of heart disease. However, high-quality observational evidence has challenged this assumption, suggesting the relationship may be more nuanced than previously thought.

Siri-Tarino PW et al. (2010). “Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

This comprehensive meta-analysis pooled data from 21 high-quality prospective epidemiologic studies involving 347,747 participants, followed for 5–23 years, during which 11,006 developed coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, or other cardiovascular events.

Key findings:

Comparing the highest versus lowest categories of saturated fat intake, there was no significant association with risk of CHD (relative risk: 1.07), stroke (relative risk: 0.81), or overall cardiovascular disease (relative risk: 1.00).

The results remained consistent after adjusting for potential confounders and in sensitivity analyses.

The authors concluded that there is insufficient evidence from prospective studies to support guidelines recommending restriction of saturated fat intake to reduce cardiovascular risk.

Okuyama H et al. (2011) – “New Cholesterol Guidelines for Longevity (2010).” Published in World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics.

This review and guideline proposal analyzed large Japanese population cohorts (including studies in Isehara with ~26,000 participants and national data on stroke patients) to examine the relationship between cholesterol levels and longevity.

Key findings:

Lowest all-cause mortality was observed in men with LDL cholesterol levels between 100–160 mg/dL; mortality rates increased significantly below 100–120 mg/dL.

Higher cholesterol levels were associated with milder stroke symptoms and better post-stroke survival.

Cholesterol appears to play protective roles (e.g., in cell membrane integrity, hormone production, and immune function).

The authors argue that aggressively lowering cholesterol may harm longevity in certain populations, challenging the "lower is always better" paradigm, and propose revised guidelines reflecting these observations in Japanese cohorts.

Anderson KM, Castelli WP, Levy D (1987). “Cholesterol and mortality. 30 years of follow-up from the Framingham Study.” JAMA.

This analysis examined 30-year outcomes in Framingham Heart Study participants initially free of cardiovascular disease, focusing on the relationship between baseline serum cholesterol and long-term mortality.

Key findings:

Under age 50, higher cholesterol was strongly associated with increased 30-year overall and cardiovascular mortality.

In older adults (particularly the elderly), there was no association or an inverse relationship between cholesterol levels and mortality.

Approximately half of heart attacks occurred in individuals with normal or low cholesterol levels.

The authors highlight that cholesterol's predictive value diminishes with age and that many cardiovascular events occur despite favorable cholesterol profiles, underscoring nuanced roles in aging populations.

Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) Research Group (1982). “Multiple risk factor intervention trial: risk factor changes and mortality results.” JAMA.

This large randomized primary prevention trial involved 12,866 high-risk men aged 35–57, assigned to either intensive multifactor intervention (cholesterol lowering, blood pressure control, smoking cessation) or usual care.

Key findings:

The intervention group achieved greater reductions in risk factors (e.g., cholesterol, blood pressure, smoking).

Coronary heart disease mortality was slightly lower in the intervention group (7.1% relative reduction), but this was nonsignificant.

Overall mortality was actually higher in the intervention group, driven by non-cardiovascular causes in certain subgroups.

The authors note that while risk factors improved, the trial did not demonstrate clear mortality benefits from aggressive multifactor intervention, raising questions about the expected gains from intensive cholesterol lowering in high-risk men.

How to Lower Cholesterol Naturally: Evidence-Based Approaches

Here's a look at some promising research for managing cholesterol naturally:

1. The Dietary Portfolio for Cholesterol: As Effective as Statins

In a landmark study, a "dietary portfolio" combining plant sterols, soy protein, viscous fibers, and nuts was found to lower LDL cholesterol by approximately 28–35%, an effect comparable to that of a 10–20 mg dose of early statins like lovastatin (Jenkins et al., 2003).

What Is in the Dietary Portfolio?

Plant Sterols (1–2 g total daily) These natural compounds compete with cholesterol for absorption in the gut, reducing LDL by 8–10% on their own (sources include nuts and seeds, whole grains and cereals, and legumes.)

Soy Protein (25 g total daily) Replace some animal protein with soy to lower cholesterol production in the liver.

Viscous (Soluble) Fibers (10 g total daily) These gel-forming fibers trap bile acids and cholesterol in the intestine. Top sources include oats and oatmeal, barley, psyllium husk, legumes, apples, okra, eggplant, and Brussels sprouts.

Almonds (or other tree nuts) (20–25 g total daily) A small handful of almonds (or walnuts, pistachios, etc.) provides healthy fats, fiber, and plant sterols that improve cholesterol levels and support heart health.

2. Oat Beta-Glucan Benefits: How Oatmeal Lowers Cholesterol

Oat beta-glucan (OBG), a soluble fiber found in oats, is well-known for its cholesterol-lowering benefits. A recent study found that drinking a beverage with 3 grams of OBG daily for 4 weeks significantly lowered LDL cholesterol (Othman et al., 2022).

One and a half cups of cooked oatmeal or three packets of instant oatmeal contain approximately 3 grams of OBG.

Add oats to your morning smoothie for convenience.

Some specialized barley lines, such as BARLEYmax®, contain higher levels of beta-glucan.

3. Green Tea and Cholesterol: The Power of EGCG

A systematic review of 17 studies found that consuming 107-856 mg of Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a powerful antioxidant in green tea, resulted in a reduction of LDL cholesterol over 4-14 weeks (Momose et al., 2016).

Aim for 2-3 cups of green tea daily. Note that the EGCG content in green tea can vary depending on the type of tea and brewing method.

Consider green tea extract supplements if you don't like green tea or can't drink enough.

4. Psyllium and Other Soluble Fibers for Cholesterol Reduction

A study showed that a water-soluble dietary fiber (WSDF) mixture can be beneficial, lowering LDL cholesterol by binding bile salts and reducing blood glucose levels. In the study, taking a specific fiber mixture three times daily lowered plasma total cholesterol by 10% and LDL cholesterol by 14% (Jensen et al., 1993).

Each 5-gram serving contained:

Psyllium (2.1g)

Pectin (1.3g)

Guar gum (1.1g)

Locust bean gum (0.5g)

A Holistic Approach to Heart Health: Beyond Cholesterol Numbers

The conversation around cholesterol and heart disease is evolving and we should approach the emerging evidence with an open mind. While traditional views have emphasized LDL cholesterol as the primary villain, some researchers suggest a more complex picture where arterial damage may precede cholesterol accumulation. This doesn't mean we should ignore cholesterol levels, but rather place them in a broader context of cardiovascular health.

A holistic approach to heart health might include:

Address root causes of arterial damage: Focus on inflammation, high blood sugar, insulin resistance, and oxidative stress.

Implement evidence-based natural interventions: Combine approaches like the "dietary portfolio," oat beta-glucan, green tea, and high fiber diets alongside a pharmaceutical approach.

Recognize individual variation: Very low cholesterol isn't necessarily better for overall health and longevity.

Work with healthcare providers: Have informed conversations about your individual risk factors and treatment options based on what's truly best for your individual health.

Understanding the complexities and controversies surrounding the cholesterol hypothesis empowers you to have more informed conversations with healthcare providers and make decisions that are truly best for your individual health. While high LDL cholesterol shouldn't be dismissed entirely, emerging research suggests it may be one piece of a much larger cardiovascular health puzzle that includes arterial inflammation, blood sugar management, and oxidative stress.

Bibliography

Anderson KM, Castelli WP, Levy D (1987). Cholesterol and mortality. 30 years of follow-up from the Framingham Study. JAMA, 257(16), 2176–2180. DOI: 10.1001/jama.1987.03390160062027.

Herrmann J, Lerman LO, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Holmes DR, Richardson DM, Ritman EL, Lerman A (2001). Coronary vasa vasorum neovascularization precedes epicardial endothelial dysfunction in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Cardiovascular Research, 51(4), 762–766. DOI: 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00347-9.

Jenkins DJA, Kendall CWC, Marchie A, Faulkner DA, Wong JMW, de Souza R, Emam A, Parker TL, Vidgen E, Trautwein EA, Lapsley KG, Josse RG, Leiter LA, Singer W, Connelly PW (2003). Effects of a dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods vs lovastatin on serum lipids and C-reactive protein. JAMA, 290(4), 502–510. DOI: 10.1001/jama.290.4.502.

Jensen CD, Spiller GA, Gates JE, Miller AF, Whittam JH (1993). The effect of acacia gum and a water-soluble dietary fiber mixture on blood lipids in humans. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 12(2), 147–154. DOI: 10.1080/07315724.1993.10718295.

Momose Y, Maeda-Yamamoto M, Nabetani H (2016). Systematic review of green tea epigallocatechin gallate in reducing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels of humans. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 67(6), 606–613. DOI: 10.1080/09637486.2016.1196655.

Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group (1982). Multiple risk factor intervention trial: Risk factor changes and mortality results. JAMA, 248(12), 1465–1477. DOI: 10.1001/jama.1982.03330120023025.

Nakashima Y, Fujii H, Sumiyoshi S, Wight TN, Sueishi K (2007). Early human atherosclerosis: accumulation of lipid and proteoglycans in intimal thickenings followed by macrophage infiltration. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 27(5), 1159–1165. DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.134080.

Okuyama H, Hamazaki T, Ogushi Y (2011). New Cholesterol Guidelines for Longevity (2010). World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics, 102, 124–136. DOI: 10.1159/000327834.

Othman RA, Moghadasian MH, Jones PJH (2011). Cholesterol-lowering effects of oat β-glucan. Nutrition Reviews, 69(6), 299–309. DOI: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00401.x.

Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Rifai N (2000). C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(12), 836–843. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421202.

Sachdeva A, Cannon CP, Deedwania PC, LaBresh KA, Smith SC Jr, Dai D, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC (2009). Lipid levels in patients hospitalized with coronary artery disease: An analysis of 136,905 hospitalizations in Get With The Guidelines. American Heart Journal, 157(1), 111–117.e2. DOI: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.010.

Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM (2010). Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(3), 535–546. DOI: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27725.

Subbotin VM (2016). Excessive intimal hyperplasia in human coronary arteries before intimal lipid depositions is the initiation of coronary atherosclerosis and constitutes a therapeutic target. Drug Discovery Today, 21(10), 1578–1595. DOI: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.05.017.