Should You Take Probiotics with Antibiotics?

For most of us, antibiotics feel like a double-edged sword. At times they’re necessary to get a handle on an infection, so on these occasions, we dutifully endure the gurgling in our stomach and the intestinal chaos, all the while wondering about the collateral damage accumulating in our microbiome. We finish our course, and our instinct is to immediately start a probiotic to undo the damage and restore our gut’s equilibrium.

On the surface, it sounds perfectly logical. Antibiotics kill bacteria (good ones included), whereas probiotics help bacteria recolonize a damaged microbiome.

The reality, though, is far messier than that tidy little equation suggests.

What the research actually shows depends heavily on what you're trying to accomplish. Preventing diarrhea while you're on antibiotics is a different question from restoring your microbiome afterward, and the strategies point in different directions. Timing, strain, age, health status, and diet all shape whether probiotics help, do nothing, or in some cases, actively slow your recovery.

If You Want to Prevent Diarrhea, Start Early

The most well-supported reason to take probiotics alongside antibiotics is preventing antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD), and the evidence behind it is substantial. A 2012 systematic review and meta-analysis in JAMA by Hempel et. al., pooled data from 63 randomized controlled trials covering more than 11,800 participants across a wide range of ages, conditions, and care settings.

Probiotic use was associated with a 42% relative reduction in AAD, with an absolute risk reduction of around 7%, translating to a number needed to treat of roughly 13. Put differently, give probiotics to 13 people on antibiotics and you prevent one case of diarrhea. That's a meaningful signal, even if it comes with caveats: trials varied in how they defined diarrhea, strain reporting was often incomplete, and safety data was inconsistently recorded across studies.

A 2021 meta-analysis in BMJ Open by Goodman et al., found a similar overall effect in adults, with a relative risk of about 0.63, and added an important nuance that how much you benefit depends on how likely you were to get diarrhea in the first place. For people at higher baseline risk, the absolute benefit is real and clinically useful. For lower-risk patients, the math becomes far less compelling.

What makes this evidence more actionable, though, is what it says about timing. A 2021 meta-analysis by Liao et. al., found that effect estimates tended to be more favorable when probiotics were started earlier relative to the first antibiotic dose rather than later in the course, though this is still between-trial inference rather than a clean head-to-head timing trial.

A 2022 meta-analysis in BMC Geriatrics, focused specifically on adults over 65, sharpened that signal considerably. Probiotics started within 48 hours of antibiotics were associated with a meaningful drop in AAD risk, with a pooled relative risk of around 0.71. Probiotics started later showed a pooled relative risk of roughly 1.06, which is statistically indistinguishable from doing nothing.

The window matters more than most people realize, and the common habit of finishing antibiotics first and then reaching for a probiotic is precisely the approach the timing data argues against.

Post-Antibiotic Probiotics Can Actually Slow Your Recovery

Taking probiotics after your antibiotic course ends feels intuitive, but at least one influential mechanistic human study suggests it may work against the very thing you’re trying to achieve.

A 2018 study by Suez et al., published in Cell, put that assumption to a direct test. After antibiotic treatment, participants were divided into three groups: one recovered on their own without intervention, one took a commercial multi-strain probiotic, and one received an autologous fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) made from their own pre-antibiotic stool. The probiotic group showed markedly delayed and persistently incomplete recovery of both their mucosal microbiome and their host gene expression compared to the group that simply waited. Spontaneous recovery was faster. The autologous FMT group recovered most completely of all.

The likely mechanism is competitive exclusion. The probiotic strains colonized the gut effectively enough to block the return of each person's native microbial community rather than supporting it. The strains in a capsule are not your strains, and in a gut that antibiotics have cleared, they can occupy the niche space your original bacteria need to reclaim. It's worth being precise about what Suez et al. actually demonstrated: this was a specific product used in a specific post-antibiotic window, and the findings shouldn't be stretched to cover all probiotic use in all contexts. Probiotics taken during antibiotics are a different scenario. Still, the study is a direct challenge to the reflex of always following a course of antibiotics with a probiotic regimen.

The diversity question complicates things further. A 2023 meta-analysis in BMC Medicine by Éliás et al. looked across randomized controlled trials measuring microbiome diversity during concurrent antibiotic and probiotic use and found no significant difference in alpha-diversity indices between probiotic and placebo groups. Preventing diarrhea and preserving microbial diversity are separable outcomes, and the evidence supports the former far more consistently than the latter.

A 2024 study by John et al. in Frontiers in Microbiomes did report that a multi-species probiotic taken during antibiotics helped alpha diversity stay stable and reduced antimicrobial resistance gene abundance, but the study was industry-affiliated and exploratory, and needs independent replication before its findings carry much weight. The American Gastroenterological Association's 2020 clinical practice guidelines reflected this complexity directly, emphasizing strain-specific and indication-specific recommendations over any blanket guidance, precisely because the evidence generalizes so poorly across different products, populations, and goals.

Diet Is Probably Your Most Powerful Tool

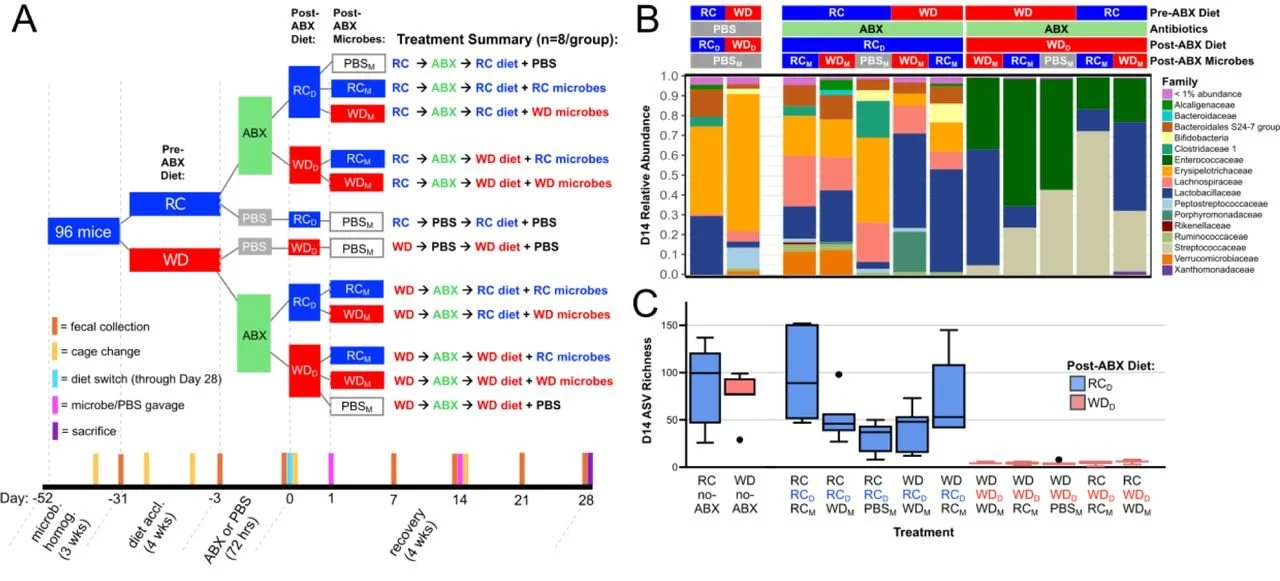

The most underappreciated variable in post-antibiotic recovery may have nothing to do with probiotics at all. Research in a mouse model suggests that post-antibiotic microbiome recovery is strongly shaped by diet. In a study in Nature by Kennedy et al., mice on regular chow began recovering phylogenetic diversity after Day 5 and had recovered over half of their initial phylogenetic diversity by Day 11, whereas mice on a Western-style diet had phylogenetic diversity that remained severely diminished through at least Day 28.

The transplant experiments within the same study were particularly telling. Switching Western-diet mice to chow after antibiotics led to substantially higher microbial richness by day 14 than staying on the Western diet. Adding a microbial transplant on top of a Western diet, though, had negligible impact on recovery. Diet appeared to be a prerequisite for robust recovery and for meaningful engraftment of new microbes in this model, whether those microbes came from a transplant or another external source.

The chow diet created conditions that supported successional recovery, consistent with a shift toward more syntrophic cross-feeding (mutually beneficial cross-feeding between microbes) interactions predicted by the authors’ metabolic modeling; the Western diet did the opposite, favoring dominance by a generalist and prolonging dysbiosis. That prolonged dysbiosis also translated into markedly reduced colonization resistance: Western-diet mice that received antibiotics carried roughly 100,000-fold higher median Salmonella loads at 24 to 48 hours after infection and showed more severe inflammatory pathology.

These are mouse data, and the translation to humans requires restraint, but the mechanistic logic aligns with what we already know from human microbiome research about how fiber-fermenting communities help stabilize and restore gut ecosystems.

It Takes Time for the Gut to Recover

Even in healthy people, the gut microbiome doesn't always snap back quickly or completely after antibiotics. A 2018 study in Nature Microbiology by Palleja et al. gave 12 healthy young men a short but intensive 4-day course of three powerful antibiotics simultaneously: meropenem, gentamicin, and vancomycin. Researchers tracked their gut bacteria using shotgun metagenomics for the following six months.

The overall community began shifting back toward normal within weeks and reached near-baseline composition at around the 1.5-month mark. Despite that apparent recovery, 9 common species that had been present in every participant before treatment remained completely undetectable in most of them at the 180-day mark. Recovery was real, but partial, and surprisingly slow for some of the key players.

Diet shapes how well and how fast things bounce back. A 2021 controlled study in Cell Host & Microbe tested this directly by putting participants on different diets after microbiome disruption, including a fiber-free synthetic enteral nutrition formula. The fiber-free diet clearly hampered recovery compared to fiber-rich ones. Without plant-based fibers to feed on, the microbiome struggled to regain its balance and metabolic function.

A separate 2021 randomized trial in Cell assigned healthy adults to either a high-fermented-food diet, including yogurt, kefir, kimchi, and kombucha, or a high-fiber diet for 10 weeks. The fermented-food group saw steady increases in overall microbiome diversity alongside drops in inflammatory markers. The high-fiber group showed shifts in the microbiome's functional capabilities, such as enzyme production, but didn't reliably increase diversity in the same way over the study period.

The two dietary approaches appear to work through different mechanisms, which suggests they complement rather than replace each other during post-antibiotic recovery. Fiber feeds the native bacteria already trying to re-establish themselves, while fermented foods introduce live microbial inputs and appear to modulate immune tone in ways that fiber alone doesn't consistently replicate.

What the evidence supports, taken as a whole, is that recovery is an active process that responds to diet in measurable ways, and that the standard Western pattern of low fiber and minimal fermented food is about the worst environment you could offer a microbiome that's trying to rebuild.

References

Hempel S, Newberry SJ, Maher AR, et al. Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;307(18):1959-69. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.3507.

Goodman C, Keating G, Georgousopoulou E, Hespe C, Levett K. Probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8):e043054. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043054.

Liao W, Chen C, Wen T, Zhao Q. Probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in adults: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(6):469-80. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001515.

Zhang L, Zeng X, Guo D, Zou Y, Gan H, Huang X. Early use of probiotics might prevent antibiotic-associated diarrhea in elderly (>65 years): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):562. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-03257-3.

Suez J, Zmora N, Zilberman-Schapira G, Mor U, Dori-Bachash M, Bashiardes S, et al. Post-antibiotic gut mucosal microbiome reconstitution is impaired by probiotics and improved by autologous FMT. Cell. 2018;174(6):1406-23.e16. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.047.

Éliás AJ, Barna V, Patoni C, et al. Probiotic supplementation during antibiotic treatment is unjustified in maintaining the gut microbiome diversity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2023;21:262. doi:10.1186/s12916-023-02961-0.

John D, Michael D, Dabcheva M, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study assessing the impact of probiotic supplementation on antibiotic induced changes in the gut microbiome. Front Microbiomes. 2024;3:1359580. doi:10.3389/frmbi.2024.1359580.

Su GL, Ko CW, Bercik P, et al. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the role of probiotics in the management of gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(2):697-705. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.059.

Kennedy MS, Freiburger A, Cooper M, Beilsmith K, St George ML, Kalski M, et al. Diet outperforms microbial transplant to drive microbiome recovery in mice. Nature. 2025;642(8068):747-55. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-08937-9.

Palleja A, Mikkelsen KH, Forslund SK, et al. Recovery of gut microbiota of healthy adults following antibiotic exposure. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:1255-65. doi:10.1038/s41564-018-0257-9.

Tanes C, Bittinger K, Gao Y, et al. Role of dietary fiber in the recovery of the human gut microbiome and its metabolome. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29(3):394-407.e5. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2020.12.012.

Wastyk HC, Fragiadakis GK, Perelman D, et al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell. 2021;184(16):4137-53.e14. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.019.